30 years after the ‘Peaceful Revolution’ in East Germany: The ‘train of freedom’ rolls again

By Sabine Volk

“Train of freedom, destination: Prague-Libeň, departure: 7.33am” says the destination board at Dresden’s Central Station on the early September morning. On the rail tracks rests a train consisting of a couple of historic wagons, a locomotive, an old-school dining car. According to the painted inscription, the train belongs to the “Deutsche Reichsbahn”, which relates, not without irony, to the national train company of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR). Several heart-shaped stickers in the colors black-red-gold shine on the dark green paint of the train. White letters announce the motto of this year’s commemoration season: “30 Years – Germany is one (thing): many (things)”*

Camping in the Embassy gardens: the GDR refugees in Prague

The historic train to Prague-Libeň station commemorates the special trains in which a couple of thousands of GDR citizens rode from Prague to Hof, a small town at the former border between the two German states, starting from the night of September 30 to October 1, 1989. The weeks and months before had been characterized by unexpected political events in the state socialist systems of Central and Eastern Europe. The Soviet Union had announced the ending of the so-called Brezhnev doctrine, campaigning for glasnost and perestroika instead. In Poland, the opposition was negotiating with the socialist government around several Round Tables. Hungary had opened its border with Austria. In this climate of political change and opening, GDR citizens who had wanted to leave the socialist state sensed their chance to go west. Since the summer, many of them had traveled to Prague, usually under the pretext of tourism or visiting friends. Instead of visiting their Czech socialist brethren, however, they made their way to the Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) in the historic Lobkowicz Palais on the northern shore of the Moldau. Hundreds of them had climbed over the Embassy’s fence and subsequently camped in the Embassy’s garden in order to pressure the GDR government to give them permission to leave the country.

In September 1989, the situation got out of hand. The numbers of refugees in the Embassy’s garden had reached nearly 4,000 people, making it impossible to provide enough food, places to sleep, hygienic facilities, and so on. On September 30, the GDR authorities finally gave in. The refugees received the permission to move to West Germany by train. The first train left Prague-Libeň station at 7.33pm, arriving in the Bavarian town Hof the next morning. In a last attempt at performing sovereignty, the GDR’s only condition was that the trains should ride over GDR-territory, more precisely through the cities of Dresden, Freiberg, and others. This was a big mistake, as became clear in the night of the train ride. Hundreds of citizens gathered at the train stations along the route, trying to jump on the passing trains sealed off by the armed police forces, and thus demonstrating their disenchantment with the socialist state.

Only about a week after the first train ride between Prague-Libeň station and Hof, the ‘Peaceful Revolution’ sped up. On October 9, the so far largest Monday demonstration took place in Leipzig. It gathered around 70,000 people who peacefully chanted ‘We are the people’ and ‘No violence’. Later that month, the General Secretary of the East German socialist party, Erich Honecker, resigned. On 9 November, the Berlin Wall fell. The collapse of the GDR seemed now unstoppable, not least triggered by the pressure put on the regime by the thousands of refugees in the Prague Embassy.

Celebrating freedom in Prague, 30 years later

On this Saturday morning, thirty years after the eventful fall of 1989, the ‘train of freedom’ rolls again between Dresden and Prague. Admittedly, it rolls (for now) in the opposite direction, but the historic décor does not fail its passengers to relive some memories. Indeed, the passengers are the refugees from back then, who were offered to take the train to Prague to participate in the Embassy’s ‘Celebration of Freedom’ in the afternoon. On the way, they share their memories with each other, as well as with students from (East) German high schools and universities. Upon arrival in the gardens of the German Embassy in Prague, many of the past refugees fight against the tears. Most of them have not been back to Prague where they spent a couple of days or weeks camping in the overcrowded Embassy’s muddy garden, not knowing if and when they would be able to leave, and if they would ever be able to return to their families and friends whom they had left behind.

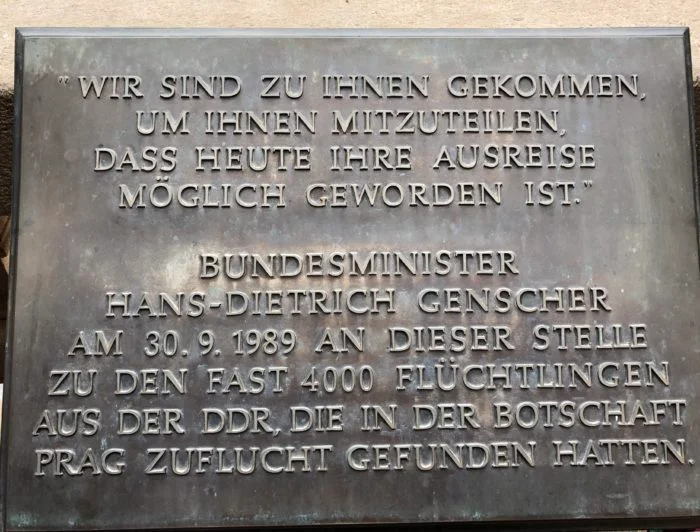

On this sunny September day, the gardens of the beautiful Lobkowicz Palais look quite different. The employees of the Embassy have spent weeks preparing this public celebration. Hence, the Baroque-style box hedge and the grass are in perfect shape, the white tents contain exhibitions about the ‘Peaceful Revolution’ and German reunification, the smell of sausages is in the air, and the visitors’ cheerful chatter makes it hard to believe that around 4,000 people had anxiously persisted in the autumnal humidity thirty years ago. The Embassy conceived a broad program ranging from film projections and photo exhibitions to discussion rounds with politicians and historians from both Germany and Czech Republic. Most importantly, there are many opportunities to get in touch with the former refugees and other witnesses, for instance in the ‘living library’ where former refugees, Embassy employees, Red Cross volunteers, and Czech neighbors share their stories. What attracts most attraction, however, is the balcony which oversees the gardens. As a large memorial tablet reminds us, it was here that the German Federal Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher announced to the refugees that they had received permission to leave to West Germany. His words, which had been drowned in the cheering of the crowd, are continuously referred to as “one of the most famous sentences of recent German history”.

The ‘Peaceful Revolution’ in German memory politics

The events between Dresden and Prague were co-organized by the Commission “30 Years Peaceful Revolution and German Unity put into place by the German Federal Government in May 2019. The task of the 22 members of the Commission is to give recommendations on how to commemorate the so-called ‘Peaceful Revolution’ in the fall of 1989 and the German reunification of October 3, 1990. While many commentators criticized that the Commission was put into place much too late – after all, one major event triggering the Revolution, namely the rigged municipal elections of May 1989 – had already passed when the Commission started operating. Yet, the 22 Commission members from German politics, civil society, and art scene, then hurried to conceive a plan. Eight ‘milestones’ on the way to German reunification will be celebrated, and dialogues with citizens will be organized in addition to the official celebrations.

The overall historical narrative offered by the German government is not hard to discern. ‘1989’ – this year embodies Germany’s only successful revolution from below which caused the demise of an unjust, repressive state socialist system and culminated in the reunification of the two German states. The Prague refugees are as much part of this ‘Peaceful Revolution’ as the long-time opposition activists and the demonstrators of Leipzig’s legendary Monday demonstrations. In fact, the current German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas referred to the announcement of the GDR’s permission for the refugees to leave the country as “the most magical moment of the German reunification next to the fall of the Berlin Wall” in his speech on September 30. The refugees were courageous enough to risk their lives “for freedom, justice, democracy”, asserted Maas.

Who owns the ‘Peaceful Revolution’?

Maas’ speech took place in the context of a recent sensitive debate polarizing GDR historians and former activists, mostly carried out in the feuilleton of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. The emotional debate concerned the question of who should take credit for the achievements of the ‘Peaceful Revolution’ – the opposition forces who had been engaged in contentious activity for years, or the mass movement which was triggered in the fall of 1989 against the backdrop of perestroika in the other socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe? Whereas sociologist Detlef Pollack argued that it was the mass movement which brought the regime to fall rather than an elitist opposition, the historian Ilko-Sascha Kowalczuk and former GDR opposition activists emotionally defended the opposition movement(s) as the driving forces behind the mass protest. Perhaps unconsciously, Heiko Maas’ speech took Pollack’s position, attributing major weight to the mass movement of people who left their socialist home behind.

In this September, thirty years after the ‘Peaceful Revolution’, there seems to be no place for a critical account of the outcome of the revolution as well as the state of German liberal democracy as such. While scientists and activists quarrel about whom to attribute the merits of the revolution to, there is little mention about much more pressing problems such as the stark rise of far-right and populist attitudes in the region of the former GDR. Indeed, Germany’s new-ish far-right populist party Alternative for Germany (AfD) is celebrating record voting outcomes in one election after the other, and has even become the strongest political force in some parts of the country in the European elections in May 2019. In particular, Saxony and its conservative capital Dresden, where the xenophobic movement PEGIDA (short for Patriotic Europeans against the Islamization of the Occident) operates for five years already, have become a hotbed for far-right populist parties and initiatives.

When the historic ‘Train of Freedom’ rolls back into Dresden Central Station in the evening, the legendary rock ballad Wind of Change by the Scorpions resonates at the platform. In 1989 and the following years, it had become the anthem of Germany’s transition. Now again one feels the wind of change in German and European politics: a draft of authoritarianism, isolation, and minority repression. Hopefully it will not become a storm.

- Tentative translation of the German original wordplay “30 Jahre – Deutschland ist eins: vieles”.