LGBT resistance to Polish populism, or “what true Poland looks like”: notes from an LGBT protest in Krakow

In early June, you might have been shocked by reading statements about the LGBT movement that made international news. I am not talking about J. K. Rowling’s tweets. I am talking about the declarations coming from members of Polish ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, and most notably from its former member and the presidential candidate they back, Andrzej Duda.

At a rally in Brzeg, Duda claimed, “They are trying to convince us that this [LGBT] is people, but this is just an ideology”. He went on to compare the promotion of LGBT rights to communist ideology, and noted that this one is “even more destructive to humans”. Shortly before this campaign speech, he signed the Family Charter — a plan to support and protect Polish families, which includes “defending children from LGBT ideology”, if he were to win the election. PiS politicians presented the presidential election as almost a civilisational choice “between white-and-red Poland and rainbow Poland”.

The resistance

On Sunday, June 21, LGBT activists in a number of Polish cities took to the streets for peaceful protests. In Krakow, as everywhere, the protest was against the Family charter, under the slogan of #StopKarcieNienawisci (“Stop the hate charter”). However, it was also a chance to make president Duda see for himself the humans behind the LGBT acronym, as that afternoon he was giving a speech on Krakow’s main square.

One side of the square, closest to Saint Mary’s Basilica, hosted Duda’s rally, and the other, the LGBT protest. Police in between the two. Despite the heavy rain, a large crowd had gathered. The LGBT protest mostly consisted of (and was organised and led by) young people, many in their late teens. Among the sea of rainbow flags and umbrellas with islands of trans, pansexual and non-binary flags, there were also occasional Polish and EU flags. As Duda’s gathering was shorter, the police were redirecting people leaving his side of the square to go around, not through, the LGBT demonstration.

Duda, a man of PiS, derogatively calling the LGBT movement an ideology is a way to discredit LGBT rights and portray them as a threat to the Polish family. The protestors came to respond to Duda’s claims and to voice their perspective. One of their signs said “We want to start families, not ruin them”. One of the speakers pointed out that at this time they “need to leave Poland to start a family”. “I have just graduated from high school, like many of you here”, a young girl stated. “I would like to stay. I love Poland, I love Krakow. But I am afraid for my life in this country”. “I love you Poland, but you are breaking my heart”, another sign read. In response to PiS’s framing of LGBT activism as a threat to children – the chairman of PiS Jarosław Kaczyński famously demanded “Hands off our children” – protestors turned the tables: “Be proud of your [LGBT] children, give them a chance… There is nothing more important than children and their future”.

Many signs and speeches were full of frustration that these young Poles feel towards national politics, but also of their desire to see a positive change, to be able to claim their place in the nation. “I live here and now”, a protestor said, implying that here and now is when they want to see a change in attitudes. There were many signs demanding equal rights: “LGBTQIA rights are human rights”, “I demand equal rights for my rainbow friends”, “Equal rights are not a cake, there is enough for everyone”.

The largest number of signs read “LGBT are people, not an ideology”, directly referencing Duda’s words. “I am a human and I am pissed off”, read one sign. A speaker said, “I am not a human in this country”. Indeed, Duda’s words were dehumanising. Christian values, which PiS allegedly adheres to, imply loving thy neighbour and treating each human as a child of God. So to justify mistreatment, you need to first dehumanise the enemy, in this case by calling them an ideology. Or, like in the case of refugees, by calling them a flooding, and using a language to describe them, comparable to the one Nazis used in regard to Jews. This is an extremely dangerous path to take, especially towards your own citizens. “My life is not your electoral slogan”, a sign said. The crowd chanted “Duda, apologise!”.

The crowd chanted “Here is Poland!”. Indeed, LGBT are also people, and they are also part of Poland. But for PiS, they are not people, and they are definitely not the ‘pure’ people constituting the ‘real’ Poland. And this is one of the great dangers of populism. Pluralism is one of its major rivals (Müller, 2016). The good news is that someone, young LGBT Poles and their allies, started challenging the somewhat hegemonic populist narrative. Even though all we read in the international news are shocking statements by PiS associates, there is another part of Poland that disagrees and is mobilising. “Enough of exclusionary discourse”, a sign said.

Populism and LGBT

What’s populist about the anti-LGBT discourse of Duda and PiS? According to Mudde and Kaltwasser (2017), populism is “a thin-cantered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic camps, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite”, and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people”. Mudde further explains populism as “a Manichean outlook, in which there are only friends and foes. Opponents are not just people with different priorities and values, they are evil!” (2004, p. 544).

Thus, it is a particularly moralistic imagination of politics, in which a morally pure, fully united yet, according to Mudde, ultimately fictional people are set against allegedly morally inferior elites. In the vision of PiS, those immoral elites are the EU, who, they say, forces member states to conform to what contravenes Poland’s traditional family values. “But that doesn’t mean we should… become infected with social diseases that dominate there [in the West]”, Kaczyński declared.

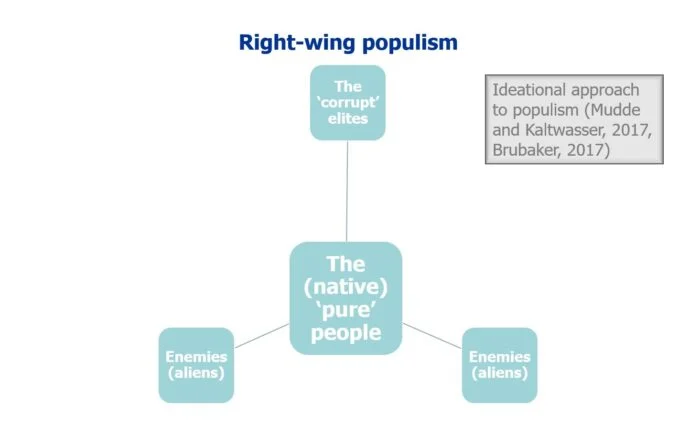

There are many types of populism, which appear from the ‘thickening’ of thin populist ideology with other concepts. A combination with nativism and authoritarianism makes (radical) right-wing populism (Mudde, 2007). It is better analysed as a triad, where the vertical binary of people versus the elite is complemented by a horizontal axis, on which the ‘good’ people are juxtaposed to and threatened by ‘enemies’ (aliens).

Moreover, the elites often ignore or even exacerbate the danger that ‘aliens’ pose. In the Polish case, we see this clearly with Rafał Trzaskowski, Duda’s main rival in the presidential run, whom PiS and PiS-affiliated media accredit with endangering Poland with an LGBT “ideology” (the idea stemming from his signing of LGBT+ Declaration for Warsaw). Thus, the ‘pure’ people have enemies both ‘above’ and ‘outside’. This is constructed through discursive manoeuvres, which set up symbolic boundaries between the imagined groups (Kubik, 2018).

Instances of such tertiary logics have been present in all recent electoral campaigns of Law and Justice and have contributed to them winning multiple elections in a row ever since 2015. “Facing a tough election, Andrzej Duda needs enemies”. This exclusionary discourse, where they single out one group, essentially pick a scapegoat, discursively construct them as an enemy and an existential threat to the Polish nation, is designed to activate fear. “This imported LGBT movement…threatens our identity, our nation, its continued existence, and therefore the Polish state”, said Kaczyński. Once the fear is invoked, PiS is ready to jump in with the promise to save Poles from the threat, promising salvation — messianic politics is another common attribute of populism (Zuquette, 2013).

In 2015 before the parliamentary election, the ‘othered’ group, constructed into an enemy, were migrants and refugees. Before the European elections in 2019, and now in the presidential rally of 2020, LGBT people have served this purpose. Ruth Wodak has called this strategy of right-wing populists climbing the electoral ladder by means of nationalistic, xenophobic, racist or antisemitic rhetoric “politics of fear” (2015). This time, however, PiS has directed exclusionary discourse not at external ‘others’, like refugees using racist and Islamophobic rhetoric, but at internal ‘others’ ─ LGBT Poles. This has left many Polish LGBT (and not only) citizens furious and moved them enough to go out to the streets to protest.

The paradox of the ‘general will of the people’

Even though ‘the general will of the people’, which populists claim to express, might sound very democratic, it is not, because they put limitations on who ‘the people’ are. In Poland, the President, the one authority figure who can both initiate new legislation and veto adopted laws, has explicitly stated that non-heterosexuals are not. And it is exactly protection of minorities that is essential to a well-functioning liberal democracy, at least in its western understanding. Because that way we make sure that the will of truly all people is respected and accounted for, not just the will of certain people who are deemed proper. One of the demonstrators demanded that “Duda needs to decide if he wants to be the President of all, or just of those few who share his views”.

Even such a homogenous nation as Poland cannot be limited and essentialised to just one definition. LGBT Poles are also part of Poland, smaller in number, but just as real and present as the heterosexual Catholic families. As one demonstrator put it, “This is what real Poland looks like”. The people of Poland may be of different religions or none at all, liberal or conservative, straight or gay, vegetarian or carnivores — there are surely many versions of ‘Polishness’ and many identities. But at least three things they surely all have in common though: 1) they are all people, 2) they are all Polish, 3) they have a right to have their will expressed and their rights secured.

This research is part of a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 765224.