Nazi emergency? About the difficulties of addressing the problem of rising far-right extremism in Dresden

By Sabine Volk

A controversial motion entitled “Nazi emergency” passed a voting in the municipal council of Dresden. The news caught vast media attention well beyond the German borders. Sabine Volk researched the background and meaning of the motion, looking at both Dresden’s problems with the Nazis and the city’s efforts to foster democratic and pluralist values in the civil society.

A middle-sized city in the German eastern periphery does not often attract the attention of the international media. Dresden, a city with around 530,000 inhabitants in the region of Saxony, recently managed to do so –to the discontent of many Dresdeners. International media from CNN to the BBC reported that Dresden “declared a Nazi emergency”, illustrating the articles with photos from far-right extremist demonstrations in the city. What had happened?

The city council’s declaration

The press reports referred to a motion entitled “Nazi emergency? – Declaration for the joint action against antidemocratic, antipluralistic, misanthropic and right-wing extremist developments in Dresden’s society – strengthening of the civil society” (available on the website of The Green Faction Dresden which passed a voting in Dresden’s municipal council on 30 October. The motion had initially been launched by councilor Max Aschenbach from the satire party “The PARTY” (Die PARTEI), shortly after the communal elections in May 2019. He had chosen the term “Nazi emergency” (in German: Nazi-Notstand) in the context of the debates about a “climate emergency” which several German communes had declared over the past months. In interview with the local newspaper, Aschenbach explained that the term was supposed to “annoy the Greens” who “surely would want to declare a climate emergency”. Allegedly, his motion was part of a deal: he would give his vote to pass a motion on the “climate emergency” if the parties from the left-wing and green factions gave their vote to his motion on a “Nazi emergency”.

Although the initial motion and specifically the notion of “Nazi emergency” triggered criticism in the city council, the Social Democrats (SPD), the Left (LINKE) and the Green Party (BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN) finally decided to support a jointly revised version. With the additional votes of the Liberal Democrats (FDP) and three non-attached councilors from the Pirate Party and the Free Citizens, the motion passed the voting procedure. The motion’s three pages express the council’s general commitment to strengthening democratic and pluralist values in Dresden. It states clearly that Dresden has a problem with far-right extremist positions not only at the margins of the society, but at its very core, and declares the council’s commitment to emphasize democratic and pluralist values over the running legislative period 2019-2024. Although even the left-wing parties were unhappy with Aschenbach’s notion of a “Nazi emergency”, they kept the initial title. The explanation is purely technical – once a motion has been launched, the title cannot be changed anymore. If the council changes the title, the law treats the motion as new. Yet, if its content equals an earlier motion, six months have to pass in order to launch and vote upon this new motion. Hence, the city councillors from the left-wing and green party factions preferred to speed up the process, putting up with the controversial term.

Does Dresden have a Nazi emergency?

The motion triggered public outrage amongst Dresden’s population. Many citizens’ verdict is that “the city council has gone crazy”, as reports the local newspaper Sächsische Zeitung. While some question the integrity of the city council, particularly of the “leftist-green councillors”, many worry about the public image of the city. Dresden is a touristic hotspot which attracts numerous visitors specifically with its picturesque Christmas markets in the winter months. The negative PR could tangibly harm this year’s business. Indeed, the tourism association already confirmed a not specified number of cancelled vacation trips.

Yet, Dresden undoubtedly has a problem with (neo-)Nazis. Since the late 1990s and 2000s, Dresden has been a stage and hotbed for different kinds of far-right extremist mobilization. For almost a decade between 2000 and 2010, far-right extremists and neo-Nazis from all over Europe gathered in Dresden on or around the date of 13 February. Up to 6,000 far-right extremists marched in the city center to usurp the commemoration of the bombing and destruction of Dresden towards the end of the Second World War, propagating a narrative of German victimhood. While the city’s civil society only slowly managed to mobilize pro-democratic counter-demonstrations and the number of neo-Nazis finally dropped, Dresden has become the center of a new kind of far-right mobilization since 2014. For around five years now, the far-right populist movement PEGIDA organizes xenophobic and Islamophobic marches in Dresden’s city center on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. It mobilized up to 20,000 demonstrators against the ‘Islamization of the Occident’ in January 2015. Whereas the movement claims to be non-extremist and politically moderate, its co-founder and spokesperson Lutz Bachmann is regularly accused of rabble-rousing. Last but not least, the far-right populist party Alternative for Germany (AfD), which is on the rise across Germany, is now the third strongest faction in Dresden’s city council. The AfD’s ideology combines national-conservative politics with racist and antipluralist, as well as authoritarian and anti-democratic positions. Against a directive from the national party presidency, AfD politicians from all over (East) Germany have openly declared and showed their support for PEGIDA, leaving no doubt of their far-right extremist positions and political program.

Criticism from the conservatives and the far-right

Despite Dresden’s obvious problem with far-right extremism, two party factions voted against the motion in Dresden’s city council: the conservative Christian Democrats (CDU) and the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD). CDU councilor Peter Krüger harshly criticized the motion and the majority of left-wing and green parties who supported it. It is difficult to distinguish his tone, particularly his depreciating talk about “leftist battle rhetoric” and “verbal escalation”, from the AfD’s typical anti-leftist propaganda. Indeed, the AfD moans that the “leftist majority in the city council splits civil society” on its local faction’s website. A dramatically colorful image accompanies the post, featuring Dresden’s famous historically reconstructed Frauenkirche in an at least partly photo-shopped thunderstorm. Just one click away is the AfD’s proposal for a ‘substituting motion’. On a single page, this motion appeals to the city council to condemn “all kinds of extremism”. Whereas this sounds like a morally irreproachable position, observers of the AfD know well what the party seeks to express with this formulation: that the true problem of Dresden is not far-right, but far-left extremism. Yet, the statistics regularly published by the Saxon Agency for the Protection of the Constitution say something else: far-right extremism dominates over far-left extremism in Saxony. What an irony that the AfD’s proposal for a revised motion still has to carry the term “Nazi emergency” in its title.

CDU and AfD quickly received back-up. The far-right populist movement PEGIDA voiced its outrage during its latest demonstration on 4 November. “Everybody is a Nazi today”, complained one of the speakers. He did not seem to realize the contradiction when referring to the leftist counter-demonstrators as “leftist-green fascists” just a couple of minutes later. The next day, PEGIDA condemned the “meaningless and mindless motion” on the movement’s website. The post ridicules Dresden’s mayor Dirk Hilbert (FDP) whose own liberal-democratic party – although usually unlikely to vote together with the leftist-green bloc – voted for the motion during his absence. Hilbert, by the way, did not back the motion, but declared not to take part “in any linguistic escalation”. At the same time, the far-right news portal with the telling name “Politically Incorrect” picked up the news from Dresden. Not without a point, the post refers to the declaration as a ‘satire motion’, addressing Max Aschenbach’s belonging to the satire party ‘The PARTY’. Yet, “Politically Incorrect” would not fulfil its purpose if not also associating Aschenbach with “far-left extremism”. The CDU is in good company.

Dresden’s efforts against far-right extremism

The motion partially neglects the efforts already done to prevent increasing far-right extremism in Dresden. This applies even more to its press coverage. The press has usually omitted the question mark behind the controversial term of “Nazi emergency”, and interpreted the motion as declaring rather than addressing a Nazi emergency. In fact,Dresden already engages in the prevention of far-right extremist attitudes in the society. Back in 2010, the city kicked off the local action program “We develop democracy” in cooperation with the federal program “Live Democracy!”. The program aims to reduce racist, anti-Semitic and homophobic positions in the society. Therefore, it allocates financial resources to local initiatives and associations which engage with the integration of immigrants, minority rights, a democratic commemoration culture, etc.

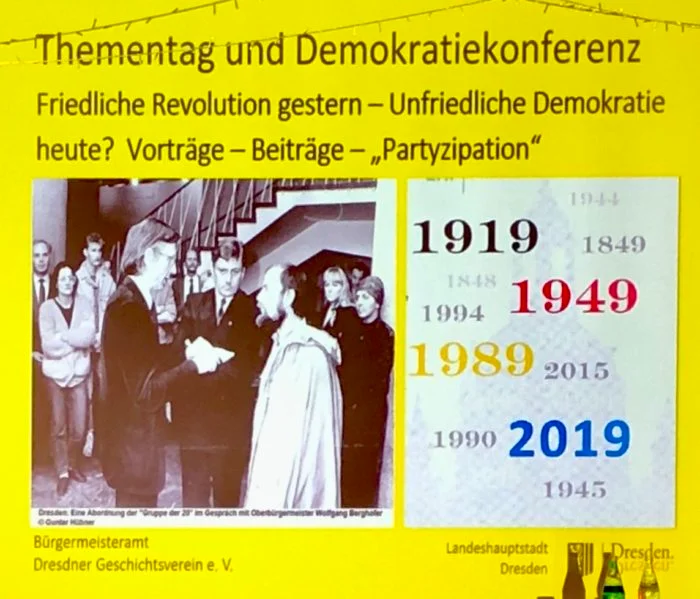

An important event of the local action program is the annual Democracy Conference. This year’s conference gathered representatives of the municipal politics and administration, notably the mayor and the city council’s consultant for democracy and civil society, scholars, civil society representatives as well as interested citizens. In light of the thirtieth anniversary of the East German ‘Peaceful Revolution’ against the state socialist regime celebrated in the fall of 2019, this year’s Democracy Conference was entitled “Peaceful Revolution yesterday, unpeaceful democracy today?” Amongst other topics related to the practices and history of liberal democracy in Germany, the conference also addressed the city council’s motion and the “Nazi emergency”. The participants did not even argue about if there was an emergency – after all, many of the civil society representatives have been campaigning against far-right extremism for years. Nevertheless, they had to admit that their efforts have not yielded (m)any positive results. Indeed, PEGIDA’s demonstrations are still mostly accepted by the urban society, gathering little counter-protest. The AfD has increased its representation in local and regional democratic institutions. Far-right extremist motivated hate crimes have increased over the past years. Hence, it seems that the local action program “We develop democracy” has had an overall negative outcome. This is particularly unsettling since the program was launched in the immediate aftermath of an incredibly violent Islamophobic murder of the Egyptian woman Marwa El-Sherbini by a Russian-German far-right extremist in 2009, a case which shocked the German and international public.

It bears important historic symbolism that Dresden’s Democracy Conference 2019 takes place on a 9 November. Without exaggeration, the 9 November is the most emotional and ambiguous date in German mnemonic culture. It is known as the Germans’ ‘fateful day’ (Schicksalstag der Deutschen) due to the numerous events of historic meaning which took place on a 9 November. Amongst them are the declaration of the first democracy in Germany in 1918, Adolf Hitler’s Beer Hall Putsch in 1923, the violent anti-Semitic November Pogroms in 1938, as well as the Fall of the Berlin Wall on 1989 which introduced the demise of the state socialist system of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), a precondition for the German Reunification in 1990. But the joy is clouded in Germany, also in the year of the thirtieth anniversary of this positively remembered ‘Peaceful Revolution’. Against the backdrop of a recent anti-Semitic terrorist attack in Halle in East Germany, the commemoration of anti-Semitic hate crimes such as the Nazi-November Pogroms must be emphasized on this 9 November 2019. In this light, the participants of the Democracy Conference hope that the controversy related to the city council’s motion addressing a “Nazi emergency” will turn out for the best: namely, that the city council will accord further financial resources for the work of the local action program and the many civil society initiatives engaging in the fight against far-right extremism. It is obvious that new formats will be needed to re-establish dialogue within the polarized society.