The Orbán Plan

The management of the coronavirus crisis in Hungary will be vastly consequential not only for the “usual” macroeconomic reasons. It is a high-stakes test for Orbán’s hold on power, his particular brand of authoritarianism.

It is by no mistake that the Hungarian public broadcaster’s news channel M1 is airing lengthy segments about market speculation in the 1990s in the midst of the Coronavirus pandemic. In the spotlight, there is one certain person: the Hungarian-born American Jewish financier, George Soros. Only relatively well-known in post-transition Hungary, he was turned into a real household name at the height of the “migration crisis” in 2015 by the government and its friendly media. They say he has an evil master plan to flood Europe with Muslim migrants and to replace the native Christian population. It is an existential war which needs to be fought tooth and nail, as PM Viktor Orbán has been relentlessly saying ever since. Christian freedom needs to be defended. And war is peace.

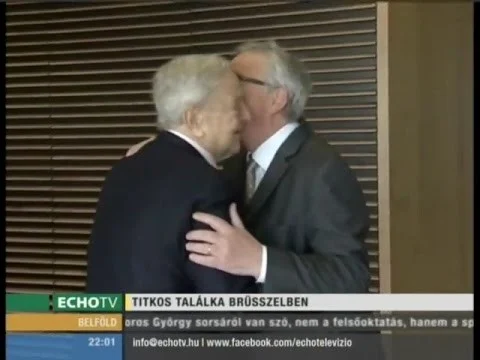

Hungarian opposition did rather little to counter the PM’s ideas: they tried to deny that the Soros Plan exists — only to be constantly disproven by pro-government media showing footages of cordial meetings between Mr. Soros and EU Commission President Juncker in Brussels over and over again. Thus the PM’s Fidesz party successfully legislated — amongst others — the “Stop Soros” laws in 2018 to curb the businessman’s sinister influence in Hungarian and European politics — and limit civil society critical to the government.

Orbán’s fight against Hungary’s own Goldstein, the bogeyman’s signature plan will not go away because of the coronavirus pandemic, but relegated for the time being in favour of public health and economic crisis management. So more than ever, there is a need for a new plan. Hungarian Government policy packages have been for some time called “defence action plans” whether employment (munkahelyvédelmi akcióterv) or family (családvédelmi akcióterv) policies. Pro-government commercial television channel TV2’s news programme already called the new pandemic crisis management policy package the “Orbán Plan” once. It is doubtful that the one-time utterance of the Orbán Plan will stick as a ubiquitous label. Nevertheless, the management of this crisis will be vastly consequential not only for the “usual” macroeconomic reasons. It is a high-stakes test for Orbán’s hold on power, his particular brand of authoritarianism.

Nevertheless, it is also a test that he will in all likelihood confidently pass. Even economic crises are only partially about the economy — running, in our times, on fiat money. Mass expectations, beliefs: feelings, hopes, and dreams about the future play a crucial role. And Orbán’s Fidesz government has a strong grip on those thanks to their mass media capture — stronger than anywhere else in Europe.

The economics of knowing

Of course, the global epidemic now forces the Fidesz government’s hand in matters of economic policy straight back into crisis management mode. What has been publicly announced about the economic measures of the “Orbán Plan” so far is rather opaque — which is, perhaps, still fair at this early stage. The known measures mostly ambition maintaining financial liquidity mainly on the supply side applying both fiscal and monetary policy measures. They include an elective credit payments suspension for all and a few urgent social measures (e.g. workers on unpaid leave can now remain within the social insurance scheme). Mostly, it is employers, companies whose administrative requirements are being relaxed and receive favourable treatment in the forms of tax reliefs, faster tax return payments, and benefits in hard-hit sectors (e.g. tourism, entertainment, media services), etc. New credit schemes have been announced from both the government and the Hungarian National Bank which target SMEs’ future activities and financial viability. Wage complements for those who are re-designated as part-time workers (and for “kurzarbeit”, “short jobs”) while aim to cover 70% of original salaries, they are not as generous as in some western European countries. The National Bank also quasi-increased the interest rate. The PM expects that these and subsequent measures will re-shuffle as much as 20% of Hungary’s national economy.

The announced crisis management measures were not published in a single package, with elaborate details, but in several parts by different sources, with key details still being rolled out. Since the two-thirds Fidesz parliamentary supermajority authorised PM Orbán’s government to rule by decree, some policies are simply issued overnight appearing in the official journal of Hungary. Not without controversy and concerns.

But minds of Hungarians these days are, rather, directed to other issues.

In what may appear as confusing to external observers, PM Orbán called the pandemic an injustice to his government and the nation: just as Hungary was finally put back on the right track, an invisible global enemy once again threatens the nation. He remains steadfast in realising the goal of a “work-based society” (munkaalapú társadalom) vowing to create more jobs than the crisis takes away. The PM personally announced not only the optional suspension of credit repayments, but also a gradual re-introduction of the “13th month” pension over the next four years — an additional month’s worth of pension benefits — clearly targeting the now vulnerable senior Hungarian citizens.

Indeed, the “13th month” pension was originally introduced — and then, when the 2008 global financial crisis hit shamefully scrapped by the left-liberal predecessors of Orbán’s government. Hungarians are frequently reminded of that botched crisis management of the previous “era” by the government and its friendly mass media outlets. Hungarians are reminded that the second, third, and the current fourth Orbán cabinets which have been enjoying a two-thirds legislative supermajority for an unprecedented ten years now originate in the post-2008 crisis economic management.

In a mixture of controversial policies termed “unorthodox economic policy” (unorthodox gazdaságpolitika) after 2010, PM Orbán’s government averted sovereign default, introduced sectoral taxes on multinational companies, repaid credits from IMF and World Bank and “sent them home”, cut down on budget deficit making it more sustainable. GDP growth hit 4–5% by the end of the 2010s — a leading figure in the laggard European environment —, unemployment went down. “Hungary performs better”. “The Hungarian reforms work”. Instead of two minutes of hate, so read omnipresent government-sponsored billboards and said frequent TV announcements on the most-watched channels, social media feeds, radio and newspaper ads.

… and ignorance

The other side of the coin goes unmentioned in much of the public debate. The government-controlled Hungarian Central Statistical Office is frequently accused of playing dirty tricks with numbers. Controversial legal measures on employment, such as the public works scheme support pro-government interpretations of the successes. But corruption is rampant. Inequality demonstrably grew while a national Fidesz-led oligarchy have formed whose members control entire sectors of the economy from agriculture through banking to media. Felcsút, the less than 2000 people village where PM Viktor Orbán grew up is now home to a light railway line and a newly established football academy with a stadium capable of hosting 3500 spectators right next door to the PM’s house. The 2014–2018 village mayor Lőrinc Mészáros is today the wealthiest person in the land: the former gas fitter credited his business successes rivalling that of Beyoncé’s not only to the fact that he may be smarter than Mark Zuckerberg, but also to “God, luck, and Viktor Orbán”.

The present pandemic-induced crisis creates a difficult new situation for Orbán and Hungary’s captured national economy. Surely, some experts agree with the “direction” of the crisis management and find it similar to other EU member state governments’ practices even if information trickles in pieces and soundbites. But many experts also dissent. Established Hungarian economists penned an open letter — signed by more than 100 experts — to the government, beyond the uncertainty, criticising the undisclosed financial resources for the crisis management policies. It is not clear how and what exactly the government wants to re-allocate: who will lose out when others “win”. They believe that government and National Bank data still rely on rosy economic forecasts denying the grave seriousness of the crisis. Indeed, the governor Matolcsy of the National Bank (former Fidesz minister of the economy) and the current minister of finance Varga talked about vastly diverging expectations. Matolcsy saw a 2–3 percent increase in the GDP, and Varga talked about an ensuing recession. Economists fear that those who are losing their jobs these days will not find solutions or relief in government policies beyond the slogans.

Thus, under the present COVID-19 pandemic, no matter how solid the Orbán cabinet’s words appear, the economic situation is being fluid. Government promises of liquidity may not help the real economy adequately, in time. But policy substance often does not necessarily feature as the first concern in news broadcasts and reports delivered to the Hungarian public.

The Orbán Plan — just as previous “defence action plans” — is not necessarily about policy content and economic effect. It is not about calm, measured crisis assessment, mitigation, and finding opportunities and ways out in a fact-based discourse. They are communicative devices designed to permeate the public sphere and Hungarian society with messages bolstering the Fidesz-led government, discrediting the opposition. Even the undetailed, sluggish publication of the policies, rather than hurting the government’s credibility, plays into Fidesz’s hands. With each new announcement, Orbán can shape the narrative, maintain control over the agenda. Policy details, content is for experts — the people will have to contend with slogans and catchphrases. “No Hungarian is alone”, and the government is here to defend the national economy and jobs. Key strata of the electorate are targeted with not only demagogic messages, but policies. The gradual re-introduction of the “13th month” pension over the next four years is a prime example: while it will cost a great deal, it does nothing to bring much needed liquidity to the population and create real demand in the next couple of years.

But senior citizens are led to believe that the government is doing what they can — in spite of ten years of corrupt leadership. Society at large is bombarded with the images of Orbán handling yet another crisis while the incompetent opposition is not only obfuscating the life-saving job of the PM, but wants to seize power for themselves and ruin the nation.

“Reality comes knocking on the door”

When you have built up a 78% dominance in the news media while in government, you do not need to make room for opposition voices, rational debate, considering alternatives, open deliberation in the policy process. Your word is, now, law.

Fidesz by now has secured a communicative hegemony. One cannot ignore it, and many only know about the news of the world from the government’s viewpoint: Fidesz slogans are on billboards, on the sides of buses and trams, on radio airwaves, in ads when one turns on the TV. Chances are, even one’s social media echo chamber is lousy with them.

Long gone are the days when policy was determined after open consultation with stakeholders and society — if there ever were any in the short history of post-communist republic in Hungary. The country is not a usual European democracy. For two years now, Freedom House evaluates Hungary as “partly free”, a first for an EU member state; esteemed researchers such as Levitsky and Way or well-known social scientist Fukuyama term it a competitive authoritarian system. Guriev and Treisman see it as an informational autocracy — similar to Turkey under Erdoğan and Russia under Putin. However, informational autocrats do also have a week spot. Since they rely on the images of strong economic performance and competent leadership rather than violence or intimidation to maintain their power unlike their 20th century predecessors, economic crises like this are existential threats to them.

An often-heard prophetic sigh of opposition-minded intelligentsia against populism has been that “reality will ultimately come knocking on the door”. One cannot rule by misdirection and lies only, people will, sooner or later, realise “what is going on”. What is going on is, however, dominantly constructed in Fidesz think-tanks, PR consultants’ and communication teams’ minds which will be, then, relayed by pro-government media editorial boards.

People, too, need leadership and organisation. There are no challengers, leaders or even a workable alternative coalition, alliance right now anywhere in sight with a chance to effectively oppose Orbán’s 10-years rule. There is little organisational, let alone institutional background to challenge Fidesz’s monopoly on the media, society, and the economy. Even the recently elected opposition hopeful, the mayor of Budapest Gergely Karácsony has little power to act without the national central government’s approval — and even less room in national media to refute the PM’s accusations that Karácsony has mishandled the pandemic because the opposition is blind sighted by power hunger. Thus the day of reckoning imagined by some of the opposition intellectuals appears to be very far off — for better or for worse.

Yet, this crisis is a severe test for Orbán’s hold on power, but he is set and ready to deal with it. For ten years, he has managed to stay on top of the agenda, fended off critique, “enemies” both domestic and international, and kept a vast network of cronies, businesses, organisations, social actors, media outlets, and politicians in line under his command. He managed to monopolise and centralise mass media communication in Hungary since 2010 — controlling the hearts and minds of key strata of the Hungarian electorate. In uncertain times, this and the resulting communicative influence, attention, and information are golden. This well-organised machinery and unchallenged leadership without a credible opposition alternative might as well survive relatively unscathed.

The Orbán Plan has thus been already complete even before the crisis happened. In it, war is still peace. Freedom can become slavery. And ultimately, ignorance — misdirected beliefs, hopes, and dreams of a nation — is its strength.