The conceptualisation and theorisation of the demand side of populism, economic inequality and insecurity

By István BENCZES, Krisztina SZABÓ, András TÉTÉNYI and Gábor VIGVÁRI

Introduction

Deliverable 5.1, entitled Report on the conceptualisation and theorisation of the demand side of populism, economic inequality and insecurity is part of Work Package 5. The aim of the deliverable is to provide a solid conceptual understanding of two factors triggering demand for populism, (income) inequality and economic insecurity, and to serve as a conceptual basis for the remaining tasks (especially for deliverables 5.2 – Database; 5.3 – Report, 5.5 – Report and 5.7 – Report) in our work package.

There is growing interest in studying how public opinion and people’s preferences are changing in favour of populist politics. Some countries have seen mounting protests against inequality and capitalist institutions leading to left-leaning policy demands often matched by similarly oriented populist supply; in others, right-wing populist movements have found increasing support for protecting the country from such “ills” of late modernity as immigrants and globalisation. There is little doubt that the demand for populism can be explained by the impact of shocks on economic conditions and social attitudes (e.g. Mutz 2018, Dehdari 2018); much less clarity exists, however, when it comes to identifying whether the populist set of ideas plays an autonomous role in electoral behaviour.

In accordance with POPREBEL’s main assumptions this deliverable treats populism as a set of ideas, a thin-centred ideology that counterposes ‘the pure people’ against ‘the corrupt elite’ and argues in turn that politics should be an expression of the general will of the people. Nonetheless, the appeal to popular sovereignty is by no means unique to populism; it is the Manichean worldview that makes populism a distinct ideology. The deliverable first briefly irons out the conceptual intricacies around the term populism and argues that populists typically exploit a representative gap based on the claim to speak for the people against the elites and substantiate their argument about the struggle between the people and the elite (Hawkins & Rovira Kaltwasser 2017). To capture this ideational element at the level of voters, scholars have introduced the concept of populist attitudes (Hawkins et al. 2012). Accordingly, populism is a latent disposition that lay dormant in individuals and is only activated under certain cues and contextual environments. The activation of populist attitudes requires a combination of two things: first, a context in which populist discourse is credible (e.g. low public trust in political institutions; representation gaps and severe failures in the provision of public services) and the use of populist rhetoric and/or performances.

The objective of the deliverable is to answer, on a theoretical ground, the following broadly defined questions: What are the typical populist attitudes and what are their relations to conventional traditional ideologies? How and under what circumstances are these attitudes activated? How can we identify the typical features of such an activating context (e.g. actual economic insecurity and inequality) and through what channels are they leading to the emergence and reproduction of populist attitudes among voters (e.g. perceived inequality and perceived economic insecurity)? Finally, if the discrepancy between the actual versus perceived conditions are large, are populist voters necessarily irrational?

Activities carried out and results

Activities carried out

- Conceptualising the terms inequality and economic insecurity;

- Providing an overview of the literature, with a special focus on the most debated academic questions associated with the two terms as triggering factors for populism;

- Providing a conceptual and theoretical framework as a basis for the remining tasks within WP5;

- Critically assessing the elements of the terms and the attempts for operationalisation.

- Presenting the preliminary and final results at the following workshops / conferences: CES Conference, June 2019, Madrid; UACES conference, September 2019, Lisbon; European Researcher’s Night, October 2019, Budapest; SVOC conference, November 2019, Budapest, CUB workshop with external reviewers from DEMOS, Budapest, December 2019.

- Publishing two contributions:

- Szabó, K. (2019): Economic inequality, In Marton, P., Thapa, M. and Romaniuk, S. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopaedia of Global Security Studies. Cham, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tétényi, A. (2019): Economic insecurity. In Marton, P., Thapa, M. and Romaniuk, S. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopaedia of Global Security Studies. Cham, Palgrave Macmillan.

Results

Fitting in the broad framework of POPREBEL, our theory of populist voting draws from an ideational definition of populism. Populism does not necessarily imply short-sighted economic policymaking (Dornbusch and Edwards 1991) and is certainly more than a cult of charismatic leaders, a type of discourse and mass appeal (Barr 2009; Weyland 2001). Populism is rather a set of ideas – namely ‘a discourse that sees politics in Manichaean terms as a struggle between the people, which is the embodiment of democratic virtue; and a corrupt establishment’ (Hawkins 2009; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2013). Within this essentialist view of politics, the world is separated into two camps with fundamentally moral distinctions: the good ‘people’ and the evil ‘elite’. The people are always praised as a virtuous, reified and homogeneous entity, whose general will should be the basis for all politics (Mudde, 2004). These people are oppressed by a powerful minority, illegitimately controlling the state for its benefit: the elites. Beyond any legitimate differences between the people and the elites, beyond the differences of opinion or interest, the only relevant political division for populism is the moral cleavage between the people and the elites.

Following the widespread acceptance of the ideational definition of populism, the researchers started going beyond populism as an elite discourse and engaged in empirical studies of attitudes that individuals hold about politics (Hawkins, Riding, & Mudde, 2012; Stanley, 2011). A number of studies use public opinion surveys to assess the extent to which the populist or proto-populist set of ideas is widespread in society and thus to understand the depth of populist attitudes in society (Schulz et al. 2018). Typically, these ideas and values resonate with some populist-sounding predispositions such as the virtue of ordinary citizens, anti-elitism, anti-migration, xenophobia etc. Recent studies have found that these attitudes (and the attitudes towards certain sets of values) are correlated with voting for populist parties, for instance in the Netherlands (Akkerman et al. 2017) and in other Western European countries (Van Hauwaert and van Kessel 2018).

What is less clear in the literature and what this deliverable is particularly interested in are the following questions: how can we position these newly invented populist attitude and the populist ideas in relation to traditional ideologies? What can activate the populist attitudes and how? And is the activation process based on a completely irrational thought processes or do voters’ populist attitudes have some rational basis?

There is much academic debate over the relationship of populist attitudes to traditional issue positions and ideologies (e.g. Hawkins et al. 2018). It remains unclear whether populist attitudes exist independently and compete with traditional issue positions and ideology, or whether populist attitude co-exists and thus are embedded in contemporary ideologies. In line with the consensus in the literature (e.g. Hawkins et al. 2018), this deliverable argues that populist ideas are not seen as a well-defined, stand-alone ideology that is usually considered as a coherent and relatively comprehensive programmatic position. While the ‘thick’ or classical ideologies, such as conservatism, liberalism or socialism, typically articulate comprehensive political programmes, populism – as well as other discourses such as nationalism or pluralism – have limited programmatic scope and is therefore a ‘thin-centred’ ideology (Mudde 2004; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser 2017). Thus, we cannot interpret or understand populism without the broader ideological context within which it operates, as these classical ideologies (or right versus left-wing ideologies) actually mediate the effect of populist ideas, whilst also providing the political means through which populist attitudes can be activated. Once these populist attitudes are activated, their interaction with the conventional ideologies cannot be disentangled.

The second part of the argument is that populist attitudes require a certain context and triggering factors that make them salient. It is a common theme in the field of political psychology (e.g. Mondak et al. 2010, Stenner 2012) that the effective presence of voters’ attitudes or dispositions depends on external triggers, while it is also widely argued that the less consciously articulated certain ideas are, the more likely that they require activation to become salient. The populist literature is unanimous in believing that populist attitudes are a set of loosely articulated ideas; thus it is reasonable to assume that they generally lie dormant and are typically activated by certain factors.

The third question relates to the context within which populist attitudes are activated and whether this context necessarily results in irrational voting behaviour. The context which is most likely to activate populist attitudes is domestic governance failure attributable to internal elite behaviour and collusion (Kriesi and Pappas 2015). The failure of domestic governance justifies the rise of populism by undermining the democratic legitimacy of the political class and by engaging dissatisfied and disenfranchised citizens, helping close the representation gap (Mudde & Kaltwasser, 2012). Populism is interpreted as a corrective to democracy that responses to the community’s problems. The establishment (in t-1) is held responsible for not fulfilling the general will of ‘the people’, and thus the anger becomes widespread across the population, which in turn triggers the activation of populist attitudes (Rico et al. 2017). Typically, an explosion of scandals showing systemic corruption reveals that the elite has been acting fraudulently, leading to the people questioning the moral foundation of the democratic order and undermining trust in the democratic system in general. In addition to this, political unresponsiveness might trigger populist attitudes among voters, as political indifference and the failure of the elites to represent the ‘people’ distance the elites from the policy concerns of the ‘people’. This distance coupled with the lack of intentionality turns quickly into social tensions through the alienation of citizens from established political actors. For instance, in Venezuela in the 1990s, people were not more populist in their outlook than any other Latin American people, but their populist predispositions were activated by a series of corruption scandals coupled with economic mismanagement and by the supply of a strong populist leader, Hugo Chávez (Hawkins et al. 2010).

What are the components of such contexts in general and of such a domestic governance failure in particular? Can we predict the typical contexts activating populist attitudes? Whilst there are numerous components of such contexts, this deliverable focuses on two of the most commonly cited factors: inequality and economic insecurity.

Economic insecurity is used as an umbrella term often encompassing some forms of (real or perceived) inequality. Economic insecurity implies “different manifestations of material well-being” (Anderson and Pontusson 2007, p. 212) that can range from job-related concerns and personal-income-based issues and to inequality. Economic insecurity is defined as “the anxiety produced by the possible exposure to adverse economic events and by the anticipation of the difficulty to recover from them” (Bossert and D’Ambrosio 2013, p. 1018), an intersection between “perceived” and “actual” downside risk. An important element of this conceptualisation is that the sense of economic insecurity may be thought to arise from perceptions of the risk of economic misfortune (Dominitz and Manski 1997, p. 264). This perception is always relative; the basis of this normative judgement is the society within which the individual lives and thus it is important to think conceptually and empirically about inequality as a determinant of economic insecurity.

Much of the debate over the rising levels of inequality is phrased in terms of income, or in terms of components of income like wages and earnings. Nonetheless, in economics, a basic utility function of individuals typically refers to consumption and leisure, not to income. The distinction between income and consumption could make a meaningful difference in thinking about inequality if the distribution of consumption at a given point in time is less wide than that of income or if its evolution over time is smoother than that of income (Attanasio et al. 2016). Another aspect of economic inequality is the distribution of wealth, which usually shows an even more unequal pattern than the distribution of either income or consumption. Distributions of factors of production – such as land or capital – are important determinants in terms of assessing the opportunities individuals have to be productive and to generate household income. It is indeed critical to divide total income into two categories of income flows: income from labour and income from capital.

Nonetheless, income or any other materialised measure does not tell us what an individual can really do and be, given his or her own characteristics. The same amount of income does not translate into an equal capacity to do the same set of activities. Acknowledging this underlying criticism against the utilitarian tradition, first in 1971, Rawls focused on the problem of choosing the correct equalisandum and proposed the notion of primary goods. Primary goods such as basic liberties and rights, access to political and other offices, income and wealth should be distributed equally within the society. Although primary goods, as proposed by Rawls, are a broader group of necessities than income in itself, they still fail to account for what an individual is capable of doing. Amartya Sen (1980, 1985, 1992) argues that instead of focusing on commodities and on the distribution of these commodities across individuals, functionings, defined as observable ‘doings and beings’ of persons should lie at the heart of our understanding. Hence, in a society, functions such as literacy, nutrition and health status should be promoted and equalised. Sen goes one step further and claims that societies should advocate for the (positive) freedom a person may enjoy. Capabilities therefore should be seen as sets of attainable functionings, from which the individual is free to choose. Sen’s view enriched our understanding of equality with concern about equity. In their papers, Dworkin (1981a, 1981b), Arneson (1989) and Cohen (1989) echo similar sentiments and claim that equity requires that factors influencing the individual’s final achievement, for which he or she cannot be held responsible, should be equalised within the society.

Consequently, the equity (or fairness) of a given distribution of achievements (say utilities, or incomes) cannot be judged by observing only the degree of inequality present in that distribution. Distributive judgments require an extended informational basis, with a special focus on how the observed outcomes were derived from the choice sets available to individuals. The same inequality in a distribution of outcomes can sometimes be judged equitable and sometimes not, depending on whether they reflect differences in choice sets.

There are many ways of measuring ‘economic insecurity’ and inequality (conceptually embedded in the term of economic insecurity) ranging from simple measures to more comprehensive aggregate indexes. The beauty of many inequality measures lies in their simplicity and starts from the same basic input: distribution. For any income, a distribution shows the number of individuals in the society and their share of the total income. The most commonly used measures of income inequality is the Gini coefficient and its graphical representation, the Lorenz curve. Data from the size distribution are the basis of drawing the Lorenz curve. Income recipients are arrayed from lowest to highest income along the horizontal axis, whilst the curve itself shows the share of total income received by any cumulative percentage of recipients (Pekins et al. 2013). In a perfectly equal society, the curve touches the 45-degree line at both the lower-left corner (0 percent of recipients must receive 0 percent of income) and the upper-right corner (100 percent of recipients must receive 100 percent of income). If only one household received income, and all other households had none, the curve would trace the bottom and right-hand borders of the diagram (perfect inequality). In all actual cases, the Lorenz curve lies somewhere in between. Derived from the Lorenz curve, the Gini coefficient[1] measures how far the income distribution of a country deviates from the perfectly equal distribution. As an alternative to the Gini coefficient, a common measure of income inequality is the so-called Kuznets ratio. To provide a more nuanced understanding of the degree of inequality between high- and low-income groups in a country, this measure shows the ratio of the incomes received by the top 20% and bottom 40% of the population. In a similar vein, the Palma ratio as a specific form of the so-called Decile Dispersion Ratio is also commonly used. The Palma ratio focuses on the differences between those in the top and bottom income brackets. The ratio takes the share of the richest 10% of the population in gross national income (GNI) and divides it by the share of the poorest 40% of the population. This ratio is readily interpretable by expressing the income of the rich as a multiple of that of the poor. However, while it ignores information about incomes in the middle of the income distribution, it is still a popular measure presenting well the growing divide between the richest and the poorest in society.

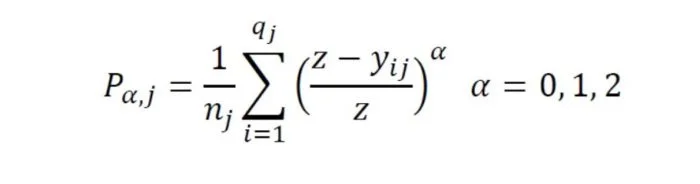

To acquire some understanding about inequality among the poorest members of a society, most economists rely on Foster-Greer-Thorbecke (FGT) poverty measures using per capita household consumption (Foster et al. 1984). For country j, the FGT measures are given by:

where Yij is per capita expenditures for household i, z is the international poverty line of $1.90 per person per day poverty line, qj denotes the number of households with expenditures below the poverty line in country j, and nj the total number of households in country j. Higher values for α place greater emphasis on the incomes of the poorest among the poor (Foster, Greer and Thorbecke, 1984), accounting for the prevalence of deep poverty among the poor.

Beyond these simple, but at the same time popular measures, there is increasing interest in more complex aggregate measures that not only measure a conceptual component of economic insecurity (some forms of inequality), but rather provide a comprehensive measure for the phenomenon. Measurement (and definition) varies accordingly from the simplest interpretation of economic insecurity as understood by unemployment and measured by the change in the unemployment rate (Algan et al. 2017, p. 319, Dustmann et al. 2017) to the more sophisticated ones such as the reported difficulty of living on current household incomes (Inglehart & Norris 2016, p. 45), or to the more complex set of factors, including unemployment in the previous three years, financial distress (finding it hard to live on the current income) and the exposure to the impact of globalisation and skill level (Guiso et al. 2018, p. 15). Osberg & Sharpe (2014, p. 71) use the Index of Economic Well-Being (IEWB), a weighted index, which measures four factors: livelihood security, security from cost of illness, security from widowhood and security in old age. Hacker et al. (2014, p. 6) also developed their own index, the Economic Security Index (ESI), incorporating three dimensions to measure economic security: income loss, medical spending shocks and the buffering effects of financial wealth. Anderson & Pontusson (2007, p. 228) associate economic insecurity with job insecurity, and measure it with individual-level survey data, estimating the probability of losing one’s current job, estimating one’s ability to find another job, and the availability of income during unemployment. Scheve and Slaughter (2004, p. 665) measure economic insecurity by responses to a specific question on job security of the British Household Panel Survey, while Burgoon and Dekker (2010, p. 131) use two types of survey answers to gauge economic insecurity: one relating to the respondent’s subjective job security, the second to the individual’s subjective income security.

While the majority of articles mentioned up to this point focused on economic security by acknowledging that it is partially due to the individuals’ subjective attitudes and how they perceive risk, Hacker et al. (2014) created an indicator, the Economic Security Index (ESI), which measures the changing economic circumstances of individuals, and not their perceptions thereof. The authors focus on those aspects which are most important in the lives of U.S. citizens: the likelihood of household income declines of 25% or higher, the probability of medical expenses, and the capacity of households to financially deal with these events. The authors use the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) and the Current Population Survey (CPS) and find that the highest levels of insecurity are experienced by those with limited education, racial minorities, young workers and single parent households.

Clearly, any theory focusing on the question of how inequality and economic insecurity can activate populist attitudes remains an empty box until one defines precisely (1) what individual achievements matter (e.g. income, wealth, political participation, job security); (2) which factors lie beyond, as opposed to within, the realm of individual responsibility; (3) whether actual inequality or rather perceived inequality lead to social grievances. In other words, for inequality and economic insecurity to become operationally or empirically meaningful in studies dealing with populism, one must decide which factors should be classified as circumstances, which should be counted as choices for which individuals are to be held responsible and whether the perception of inequality and economic insecurity is real or politically created.

Insecurity is thus understood as inequality as well as the highly subjective and exposed to individual’s perception broader social and economic context within which individuals live and interact with one another. A question naturally arises; if such insecurity generating perceptions can be altered under the impact of populist rhetoric, do populism produce irrational voting behaviour? Indeed, if the perceived conditions are rather far from the actual reality, the fear of generating irrational, exclusively emotionally driven voters is real.

The question of whether populist voters are irrational remains a debated topic in the literature, although many have found that populist voters are not necessarily irrational. For instance, Lubos Pastor and Pietro Veronesi (2018, p. 1) argues that a backlash against globalisation “emerges as the optimal response of rational voters to rising inequality, which in turn is a natural consequence of economic growth”. Pastor and Veronesi created a model, in which they define populism as the belief that a homogenous group of people living in a single country who are being victimised by an elite minority. The elite, in favour of globalisation, support free trade and similar positions. While globalisation is assumed to lead to economic growth in their model, this growth is disproportionately shared across a country’s population, mostly benefiting the elite. When inequality reaches a point where society is sufficiently strained, where economic inequality leads to stress and crime caused by economic desperation, a populist backlash takes hold. The populist response is to turn a society inward by cutting back on foreign borrowing, immigration, and trade. Thus, countries with higher inequality, more financial development, and a higher current account deficit generate a group of voters whose interests have been marginalised and who tend to support the anti-establishment populist parties. Evidence from 29 developed countries backs these predictions. The researchers claim that their model helps us understand the result of the Brexit vote and the 2016 election victory of US President Donald Trump, two of the most prominent current populist outbursts.

Conclusions

Until recently, scholars explained electoral support for populist forces by relying on measures such as support for restrictive immigration and asylum policies, the employment sector and exposure to economic globalisation or levels of trust in the traditional political institutions of liberal democracy. While these studies are helpful in that they identify why voters support particular populist parties with a well-defined policy package, this deliverable argues that there is an additional layer of ideas that politicians are expressing. The deliverable argues that populist attitudes among voters have a complementary relationship with the contemporary ideologies and are activated by certain context and by populist rhetorical tools. This deliverable is particularly interested in the question of what contexts activate populist attitudes and whether there are any well-defined components of such contexts (e.g. high income inequality, wide-spread economic insecurity).

The literature on inequality and economic insecurity as triggering factors of populism is now sizable. A number of different measurement and evaluation methods have been proposed and an even broader array of empirical applications has been undertaken. Economic insecurity as an umbrella term often encompasses some forms of (real or perceived) inequality. Economic insecurity implies “different manifestations of material well-being” (Anderson and Pontusson 2007, p. 212) that can range from job-related concerns and personal-income-based issues and to inequality. Economic insecurity is defined as the anxiety produced by the possible exposure to adverse economic events and by the anticipation of the difficulty to recover from them, an intersection between “perceived” and “actual” downside risk. An important element of this conceptualisation is that the sense of economic insecurity may be thought to arise from perceptions of the risk of economic misfortune. This perception is always relative; the basis of this normative judgement is the society within which the individual lives and thus it is important to think conceptually and empirically about inequality as a determinant of economic insecurity. Inequality has been analysed in different spheres of human life and for different domains of public policy, ranging from income distribution to wealth distribution and educational or health achievement. It is important to acknowledge, however, that inequality in income earned only tells part of the story. Hence, societies should not necessarily be concerned with decreasing income inequality but with securing for all of their members an equal chance to attain the outcomes they care about and with decreasing the (real or perceived) economic insecurity. Analysing income inequality is nevertheless a promising start, even as it tells us little about the question of how the observed outcomes derived from the choice sets available to individuals and from the income they earned. Both the conceptualisation and the operationalisation of inequality and economic insecurity remain a contested matter and are additionally subject to the vagaries of data availability, empirically. Nonetheless, deliverable 5.1. provides an insight into the changing terms of inequality and economic insecurity as well as a flavour of recent research and the operationalisation of the two terms. It is important to highlight here that the remainder of WP5 loosely follows the definition of economic insecurity provided by Bossert & D’Ambrosio (2013, p. 1018): “the anxiety produced by the possible exposure to adverse economic events and by the anticipation of the difficulty to recover from them”. At the same time, WP5 sees inequality as a term conceptually embedded in economic insecurity and assumes that both objective and subjective reasons can be found as to why the demand for populism is growing.

Bibliography

Algan, Y. et al. (2017) ‘The European Trust Crisis and the Rise of Populism’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, (Fall), 309–400. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/algantextfa17bpea.pdf.

Akkerman, A., Zaslove, A., & Spruyt, B. (2017). ‘We the people’or ‘we the peoples’? A comparison of support for the populist radical right and populist radical left in the Netherlands. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(4), 377-403.

Anderson, C. J. and Pontusson, J. (2007) ‘Workers, worries and welfare states: Social protection and job insecurity in 15 OECD countries’, European Journal of Political Research, 46(2), pp. 211–235.

Arneson, R. (1989) ‘Equality of Opportunity for Welfare.’ Philosophical Studies, 56: 77-93.

Attanasio, O. P., & Pistaferri, L. (2016). Consumption inequality. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(2), 3-28.

Barr RR (2009) Populists, Outsiders and Anti-Establishment Politics. Party Politics 15(1), 29–48.

Bossert, W. and D’Ambrosio, C. (2013) ‘Measuring economic insecurity’, International Economic Review, 54(3), pp. 1017–1030.

Burgoon, B. and Dekker, F. (2010) ‘Flexible employment, economic insecurity and social policy preferences in Europe’, Journal of European Social Policy, 20(2), pp. 126–141.

Cohen, G. A. (1989) ‘On the Currency of Egalitarian Justice.’ Ethics, 99, 906-944

Dehdari, S. H. (2018). Economic distress and support for far-right parties-evidence from Sweden. Available at SSRN 3160480.

Dominitz, J. and Manski, C. F. (1997) ‘Perceptions of Economic Insecurity: Evidence From the Survey of Economic Expectations’, Public Opinion Quarterly, 61(2), p. 261.

Dornbusch, R., & Edwards, S. (1991). The macroeconomics of populism. In The macroeconomics of populism in Latin America (pp. 7-13). University of Chicago Press.

Dustmann, C. et al. (2017) Europe’s trust deficit: Causes and remedies, Monitoring International Integration. Available at: www.cepr.org.

Dworkin, R. (1981a) ‘What is equality? Part 1: Equality of welfare.’ Philosophy & Public Affairs, 10, 185-246.

Dworkin, R. (1981b) ‘What is equality? Part 2: Equality of resources.’ Philosophy & Public Affairs, 10, 283-345.

Foster, J., Greer, j. and Thorbecke, E. (1984) A Class of Decomposable Poverty Measures. Econometrica 52: 761-766.

Guiso, L. et al. (2018) Populism : Demand and Supply. Available at: https://ideas.repec.org/p/eie/wpaper/1703.html.

Hacker, J. S. et al. (2014) ‘The economic security index: A new measure for research and policy analysis’, Review of Income and Wealth, 60(S1), pp. 5–32.

Hawkins, K. A., Kaltwasser, C. R., & Andreadis, I. (2018). The activation of populist attitudes. Government and Opposition, 1-25.

Hawkins, K. A., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2017). What the (Ideational) Study of Populism Can Teach Us, and What It Can’t. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(4), 526-542.

Hawkins, K. A., Riding, S., & Mudde, C. (2012). Measuring populist attitudes. Committee on Concepts and Methods.

Hawkins, K. A.. (2010). Venezuela’s Chavismo and Populism in Comparative Perspective. . Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Hawkins, K. A. (2009). Is Chávez populist? Measuring populist discourse in comparative perspective. Comparative Political Studies, 42(8), 1040-1067.

Inglehart, R. and Norris, P. (2016) Trump, Brexit, and the Rise of Populism: Economic Have-Nots and Cultural Backlash, HKS Working Paper No. RWP16-026.

Kriesi, H., & Pappas, T. S. (Eds.). (2015). European populism in the shadow of the great recession (pp. 1-22). Colchester: Ecpr Press.

Mair, P. (2002). Populist democracy vs party democracy. In Democracies and the populist challenge (pp. 81-98). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Mondak, J. J., Hibbing, M. V., Canache, D., Seligson, M. A., & Anderson, M. R. (2010). Personality and civic engagement: An integrative framework for the study of trait effects on political behavior. American Political Science Review, 104(1), 85-110.

Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (2017). Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Mudde, C., & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2013). Populism. In M. Freeden, & M. Stears (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of political ideologies (pp. 493–512). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mudde, C., & Kaltwasser, C. R. (Eds.). (2012). Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or corrective for democracy?. Cambridge University Press.

Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and opposition, 39(4), 541-563.

Mutz, D. C. (2018). Status threat, not economic hardship, explains the 2016 presidential vote. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(19), E4330-E4339.

Osberg, L. and Sharpe, A. (2014) ‘Measuring Economic Insecurity in Rich and Poor Nations’, Review of Income and Wealth, 60(S1), pp. S53–S76.

Pastor, L., & Veronesi, P. (2018). Inequality aversion, populism, and the backlash against globalization (No. w24900). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Perkins, D. H., Radlet, S., Lindauer, D. L., Block, S. A. (2013) Economics of Development.

Rico, G., Guinjoan, M., & Anduiza, E. (2017). The emotional underpinnings of populism: How anger and fear affect populist attitudes. Swiss Political Science Review, 23(4), 444-461.

Sen, A. (1980) ‘Equality of what?’ In S. McMurrin (ed.), The Tanner Lectures on Human Values, Salt Lake City:University of Utah Press.

Sen, A. (1985) Commodities and Capabilities. North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Sen, A. (1992) Inequality Reexamined. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Scheve, K. and Slaughter, M. J. (2004) ‘Economic Insecurity and the Globalization of Production’, American Journal of Political Science, 48(4), pp. 662–674.

Schulz, A., Müller, P., Schemer, C., Wirz, D. S., Wettstein, M., & Wirth, W. (2017). Measuring populist attitudes on three dimensions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(2), 316-326.

Stanley, B. (2011). Populism, nationalism, or national populism? An analysis of Slovak voting behaviour at the 2010 parliamentary election. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 44(4), 257-270.

Stenner, K. (2012) The authoritarian dynamic. New Jersey: Princeton University.

Van Hauwaert, S. M., & Van Kessel, S. (2018). Beyond protest and discontent: A cross‐national analysis of the effect of populist attitudes and issue positions on populist party support. European Journal of Political Research, 57(1), 68-92.

Weyland, K. (2001). Clarifying a contested concept: Populism in the study of Latin American politics. Comparative politics, 1-22.

[1] Nonetheless, collapsing all the information contained in the frequency distributions into a single number inevitably results in some loss of information as no weights are attached to the lowest quintiles that might receive less income. Another criticism of the Gini coefficient is that it is more sensitive to changes in some parts of the distribution than in others. Despite these shortcomings, the Gini index, with its simplicity, including its graphical interpretation using Lorenz curves, remains the most widely used income inequality measure.